Frankenstein (Part 1): Creating hand annotation files

NOTE: If you’re just looking for gold standard hand annotation files, scroll down to the bottom of this page.

Introduction

A few years ago—when I still wanted to major in English literature—I decided to read Frankenstein. Apart from being vaguely interested in the story, I was mainly drawn to it because of the weird 19th century Romantic drama surrounding its inception. Long story short, Percy, a 22 year old poet, meets Mary, the 17 year old daughter of a prominent British intellectual; Percy deserts his pregnant wife to party with Mary in continental Europe, where Mary participates in a ghost story competition and writes Frankenstein; Percy then edits and publishes Frankenstein before drowning off the coast of Italy.

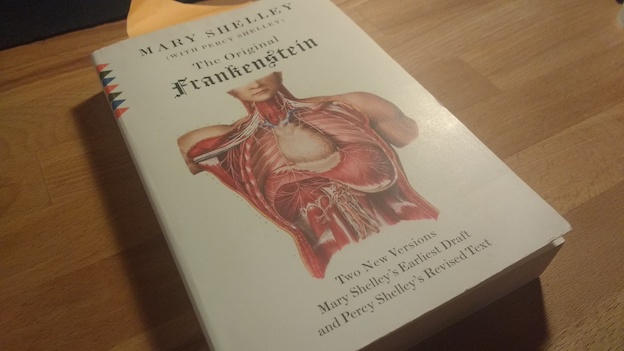

Intrigued by this story, I looked for an annotated edition of the novel that would provide additional details and context to the creation of Frankenstein. I quickly settled on this edition:

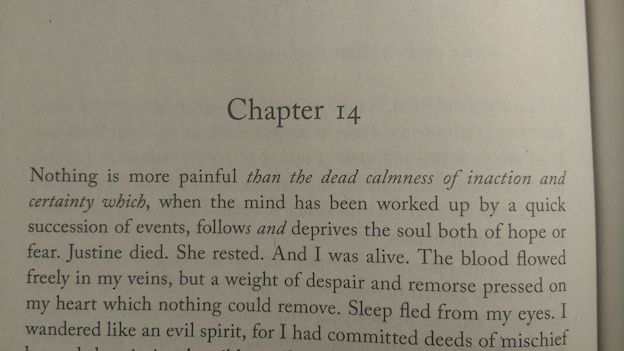

Interestingly, this edition contains two versions of the story: one version reprints the text of the first edition of the novel from 1818, and the other version was composed by the editor from handwritten drafts of Frankenstein that are held at the Oxford University library. However, the editor hadn’t stopped there. He had marked Percy’s contributions to this draft text in italics, using regular font for Mary’s writing:

The editor, Charles E. Robinson, had based this annotation on a painstaking analysis of the different handwritings and types of ink that were used in the drafts. Last year, I was suddenly reminded of these annotations when I was scrambling to find a topic for a course project. The course, which was called “Text mining”, was about the application of computer algorithms (or to use another buzzword “machine learning”) to ‘mine’ interesting information from text sources. The course had briefly touched on something called authorship attribution: feeding linguistic features of a text into computer algorithms to determine its author. I wondered whether it would be possible to use this method to arrive at an annotation of Frankenstein that was similar to the hand annotation by Robinson.

During my course project, I encountered a number of problems and questions. In this three part series of articles I’ll describe how I eventually solved these problems (long after the course was over) and found some interesting results. It is worth noting that these articles are intended ‘for dummies’ and are definitely written by a dummy; I am by no means a computer programmer or literary scholar. However, these articles will be rather detailed. So buckle up for a long read or skip to the parts you find interesting.

Getting a gold standard text

The first problem I encountered, and the topic of this first article, concerns getting a digital version of the hand annotated text by Robinson. This is more difficult than it may seem. Although an e-book version of this text exists, text mining techniques can’t deal with the e-book formats (like .azw or .epub) used by Amazon or Google. In order to make Robinson’s annotation readable by computers we would need to convert his text into programmable objects. One of the simplest ways to do this would be to create two lists (or arrays in programmer talk): one list that splits up the novel into stretches that are written by Mary and Percy respectively, and a second list with the author’s names that correspond to those stretches of text. For example, the start of Chapter 14 (in the picture above) would be represented as follows:

| Text Array | nothing is more painful |

than the dead calmness of inaction and certainty which, |

when the mind ... |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hand Array | Mary Shelley |

Percy Shelley |

Mary Shelley |

This structure can be implemented in so-called JSON files by formatting the raw text in a certain way:

- text_array.json:

["Nothing is more painful ", "than the dead calmness of inaction & certainty which", " when the mind ..."] - hand_array.json:

["mws", "pbs", "mws"]

It might be possible to convert the e-book into this format. However, often e-books are DRM-protected which would probably make this process rather frustrating. Besides, it would likely be illegal to turn the e-book version into raw text and redistribute it online. Luckily, we have an alternative source for Robinson’s annotated version: The Shelley Godwin Archive.

The Shelley Godwin Archive

The Shelley Godwin Archive (SGA) is a website that contains high quality scans and open source transcriptions of drafts written by different members of the Shelley and Godwin families. Frankenstein is one of the drafts presented on the website, and the description accompanying the draft states that:

both our transcriptions of the Frankenstein Notebooks and our attribution of authorial hand are based on Charles E. Robinson’s magisterial edition

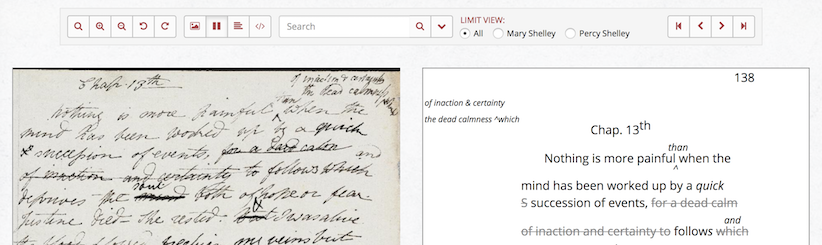

The screenshot below illustrates how the SGA presents these transcriptions:

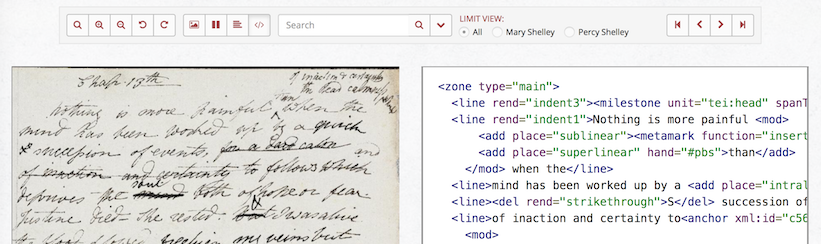

In this interface, the transcriptions on the right provide a digitized version of the scanned draft page on the left, including the changes (in italics) made by Percy when he edited the draft. However, we can’t really use these annotations as they are. First of all, they’re on a website, and second, although the changes by Percy are represented, it is not clear where they should be inserted. In other words, we need the source code of the transcriptions. The SGA actually allows you to see the code in which the transcriptions were made:

However, I needed these files locally, and luckily the SGA developers allow anyone to access them on their GitHub page. After downloading all of the files, I now had a digital version of Frankenstein with Robinson’s hand annotation on my computer, but I still had to interpret them and turn these files into the structure illustrated above.

Parsing XML files

The files I had downloaded were structured according to XML markup language. This language makes use of hierarchical structures. Simply looking at an XML file can give you a good idea of what this all means. Let’s take a look at a (slightly simplified version of) the XML code for the start of Chapter 14 (which corresponds to Chapter 13 in the draft):

<zone type="main">

<line>Chap. 13

<hi>th </hi>

</line>

<line>Nothing is more painful

<mod>

<add hand="#pbs"> than</add>

<anchor xml:id="c56-0108.02"/>

</mod> when the

</line>

<line>mind has been worked up by a

<add>quick</add>

</line>

</zone>

The hierarchy in this structure can be visualized as follows:

Each box in the figure corresponds to an element or node. The arrows represent the hierarchical relations between different nodes, where the node at the base of the arrow is the parent and the node at the pointy end is the child. For example, the three Line nodes are the children of the Zone node.

My first priority was to extract the text contained in these elements in the right order. As you can see there are 2 types of text that can be associated with an element: text and tail text. Text occurs directly after an opening <> tag, and tail text occurs directly after a closing </> tag. This is important because, as I found out, it necessitates a certain approach. My first instinct was to flatten the hierarchical structure and simply process the elements in the linear order in which they occur, see the Python code below:

from lxml import etree # lxml is a library that allows Python to handle XML structure

# assigning our example XML code to a Python lxml object

zone = etree.fromstring('<zone type="main"><line>Chap. 13<hi>th </hi></line><line>Nothing is more painful <mod><add hand="#pbs">than </add><anchor xml:id="c56-0108.02"/></mod>when the </line><line>mind has been worked up by a <add>quick</add></line></zone>')

# now we loop through a flattened list elements and extract all text, right?

reading_text = ""

for element in zone.iter():

reading_text += element.text if element.text else "" # extract text

reading_text += element.tail if element.tail else "" # extract tail text

print(reading_text)

Running the code above gives us:

Chap. 13th Nothing is more painful when the than mind has been worked up by a quick

As we can see the word than is in the wrong place. This is because we need to process the children of the <mod></mod> element before we process the tail text of <mod></mod> itself. In fact, this is a general principle that applies to every element. First we extract the regular text from a parent element, then we process the children of that element, and finally we extract the tail text of a parent element. How do we generalize this process so that we can apply it to every Frankenstein XML file without knowing how many elements it consists of and which elements contain children? The answer is a function which keeps going down the hierarchy of elements by calling itself until an element without any children (a so-called terminal node) is encountered. In other words, we need to make a recursive function:

def processElement(element):

reading_text = ""

# extract any text in element

reading_text += element.text if element.text else ""

# process children of element

for child in element:

reading_text += processElement(child) # this is the recursive part

# extract any tail text of element

reading_text += element.tail if element.tail else ""

return reading_text

print(processElement(zone))

Running the code above gives us:

Chap. 13th Nothing is more painful than when the mind has been worked up by a quick

Success! than is now in the right place! However, you will have noticed that a large part of Percy’s addition is missing from this text. This is because this addition is on another part of the page contained within its own <zone></zone> element. That zone element is referenced by the <anchor/> element in the main zone. Furthermore, we have not been keeping track of any hand changes, though it is clearly indicated in the XML code that the <add></add> element containing than has a hand attribute with the value #pbs. In other words, we can use this attribute to establish that this addition was made by Percy Bysshe Shelley.

I won’t go into detail about how I processed these features in my Python script, but the encoding guidelines used in the creation of the SGA give a nice overview of the XML side of things. In hindsight, I was really lucky to have these encoding guidelines, especially considering my limited experience with XML. They essentially gave me a systematic and detailed overview of the problems that needed to be solved, allowing me to jump right into someone else’s XML files.

Text processing

Although the XML structure in the SGA files is really useful to keep track of the changes in the manuscript and who made them, it also has certain drawbacks. Because the SGA annotators were so focussed on correctly applying the XML structure, they seemingly lost track of spaces between words when these words were contained in different elements. For example, extracting the text of the first few lines of Chapter 14 (Chapter 13 in the draft) actually results in:

Chap. 13thNothing is more painful than when themind has been worked up by a quick

As you can see, the annotators forgot to add spaces in 13thNothing and themind. Unfortunately, this problem cannot be solved by simply inserting a space between text from different elements. Consider the XML code below:

<zone type="main">

<line>took delight in her ordinary occupa</line>

<line>tions all pleasure seemed to her sacri</line>

<line>lege towards the dead— eternal woe</line>

</zone>

Both the first and the second line elements end in words that are broken off and finished in the following line. As such, implementing a rule that inserts a space between text from different elements would result in occupa tions and sacri lege respectively. This shows that we clearly need a more intelligent solution.

In certain cases we can make use of general rules. For instance, whenever a number is followed by th, as in <line>Chap. 13<hi>th</hi></line>, we know not to insert a space. However, in order to correctly extract occupations, we need to know that occupa and tions are not part of the English vocabulary. In other words, we need to make use of a dictionary if we want to process the text in the SGA files automatically.

The Datamuse API provides a programmable interface to an extensive English dictionary. This means that we can send a string of text to the Datamuse server, which then sends back a list of words that resemble the string of text we provided. For each item in this list, Datamuse also provides a relevancy score and a frequency measure. See below for the JSON object that is returned when the string occupations is sent to the Datamuse API:

[

{

"word":"occupations",

"score":129415,

"tags":["f:17.796734"]

},

{

"word":"occupation",

"score":65693,

"tags":["f:41.327097"]

},

{

"word":"occupational",

"score":356,

"tags":["f:29.288177"]

}

]

We can use these features to determine whether we should insert a space as follows:

import requests # this library allows us to make requests over the internet

import math, statistics

def callDatamuse(text):

# get the JSON object from Datamuse

output = requests.get("https://api.datamuse.com/words?sp={}&md=f".format(text))

output_list = output.json()

# get a simple list of the words returned by Datamuse:

matched_words = [i["word"] for i in output_list]

relevance = 0

frequency = 0

# check whether the text is a word that exists and

if text in matched_words:

# if so, get the relevance score and frequency of that word

word_index = matched_words.index(text)

relevance = output_list[word_index]["score"]

frequency = float(output_list[word_index]["tags"][0][2:])

# calculate a final score from relevance and the square root of frequency

final_score = relevance * math.sqrt(frequency)

return final_score

# First, let's get the score for 'no space' and store it in a dictionary object

scores = {"occupations": callDatamuse("occupations")}

# Now, lets get the score for 'insert space' and add it to the dictionary

mean_score = statistics.mean([callDatamuse("occupa"), callDatamuse("tions")])

scores["occupa tions"] = mean_score

winner = max(scores)

loser = min(scores)

print('''The correct text is '{}',

because its score of {}

is greater than the score of '{}',

which amounted to {}'''.format(winner, scores[winner], loser, scores[loser]))

Running this code gives:

The correct text is 'occupations',

because its score of 545952.3897245007

is greater than the score of 'occupa tions',

which amounted to 0.0

After some fine-tuning, the combination of this method with a number of heuristic rules turned out to be almost perfect in determining when a space should be inserted.

Composition of pages

Apart from processing the XML and text of individual pages, we also need to put these different pages into the right order. Luckily, most of this work was done by the SGA team. They provide XML files which list the pages that make up each chapter.

I adapted these files so that the composed text resembles the 1818 edition of the novel while maintaining insight in the contribution of Percy Shelley. As such, the text is taken from the 1816-1817 draft up until the last few pages of Chapter 18. From that point onwards the text has been taken from the Fair Copy so that Percy’s contributions to those final pages are reflected in the final text. As Robinson notes in the introduction to his annotated edition:

As we move from the extant 1816-1817 Draft to the first edition of 1818, we note the following differences: minor changes that Mary Shelley made to the Draft when she fair-copied it; some substantial changes that Percy Shelley made to the Draft when he wrote out the last twelve-and-three-quarter pages of the Fair Copy;

Furthermore, as Robinson notes, the following sections are missing from the 1816-1817 draft:

from Volume I, the four introductory letters from Walton to his sister Margaret and the first part of Chapter 1; and from Volume II almost half of Chapter 3 and all of Chapter 4.

I have chosen not to replicate these sections from the 1818 version as we do not know who wrote them.

Gold standard JSON files

Consecutive text by same hand

The completed Python script takes around 3-4 hours to turn all of the XML annotations into the two simple JSON arrays I wanted. These can be found below:

Sample:

# Text

["Nothing is more painful ", "than the dead calmness of inaction & certainty which", " when the mind has been worked up by a quick succession of events, follow", "s and"]

# Hand

["mws", "pbs", "mws", "pbs"]

Tokenized text

Authorship attribution and other text mining applications often derive their features from word information. In order to facilitate such analyses of Frankenstein, I have also constructed a version of the hand annotation on a word by word basis, see below for the corresponding files.

NOTE: For hand changes within a word, the word was labelled with the hand belonging to the majority of characters.

Sample:

# Text

["nothing", "is", "more", "painful", "than", "the", "dead", "calmness", "of", "inaction", "&", "certainty", "which", "when", "the", "mind", "has", "been", "worked", "up", "by", "a", "quick", "succession", "of", "events", "follows", "and"]

# Hand

["mws", "mws", "mws", "mws", "pbs", "pbs", "pbs", "pbs", "pbs", "pbs", "pbs", "pbs", "pbs", "mws", "mws", "mws", "mws", "mws", "mws", "mws", "mws", "mws", "mws", "mws", "mws", "mws", "mws", "pbs"]